This post is a part of our Making Clothes series.

Now that we’ve gone through the process of producing raw materials, turning those materials into textiles, and turning those textiles into clothing, we’re rounding out this series with a little math. Given the labor and resources that went into making one outfit, how long would it have taken to make, from start to finish, and how much land did it take to grow everything on?

Our figures here are necessarily approximate. There are too many variables to take them all into account. A good year’s flax harvest or a clumsy hand at wool-carding could make a difference to how fast workers could gather and process materials. We’re also generally working with optimistic estimates. A more thoroughly realistic assessment would have to allow for lost time and material from shrinkage, breakage, wastage, crop failures, inclement weather, and so on. We’re aiming here to get a rough sense of just how much of an investment of labor time and productive land, at minimum, one set of clothes represented in the pre-modern world.

We are also assuming a community of skilled agriculturalists and crafters who know their trade and do not need to be taught or to experiment with processes of production. The passing on of such knowledge to new generations was in itself an important part of historical agricultural and textile production, but we leave that labor out of our calculations.

Our example outfit consists of several pieces, each of which required materials and labor to make:

- A long-sleeved linen undertunic reaching to the mid-thigh

- A long-sleeved silk overtunic reaching to the knees

- Leather footwear

- A rectangular wool cloak of about knee-length

To see what it would take to produce this outfit, it is helpful to think backwards: the dimensions of our imaginary wardrobe tell us how much raw material would be needed to make it, which in turn dictates how much work would go into producing that material. We’re imagining this outfit for a person of any gender of about medium height and build. It does not represent any specific historical outfit, and does not belong to any particular place or time; a certain amount of vagueness in the design allows our outfit to reasonably stand in for clothes that could be found in many places and historical eras.

We calculate the following dimensions for the items in our wardrobe:

- Undertunic: The undertunic is made from a piece of fabric measuring 210 x 75 cm, which is cut to yield two sleeve pieces and a long piece folded poncho-style for the front and back, with a hole cut for the head. The whole piece of fabric amounts to 1.575 square meters.

- Overtunic: The overtunic is similarly cut from a piece of fabric measuring 225 x 90 cm, with two sleeve pieces and one long piece for front and back, amounting to 2.025 square meters of fabric.

- Footwear: Our shoes are made from approximately one third of a square meter or leather per shoe, thus two thirds of a square meter for a pair.

- Cloak: Our cloak is a rectangle 1 meter by 2 meters, for 2 square meters of wool.

Finished clothes

Undertunic and overtunic – The construction method of these two garments is essentially identical, so the amount of time spent cutting, sewing, and finishing each one is approximately the same. With some reconstructed historical pieces for reference, we estimate that sewing a tunic-style garment such as these takes about 6 to 9 hours. We’ll take the average of the range and estimate that each garment takes 7.5 hours to cut and sew. The two together add up to 15 labor hours.

Footwear – Leather is slower to sew than fabric, but shoes are smaller than tunics. Our shoe models have around 120 cm of seam, and reconstructions show a leather stitching speed of 50 cm per hour. Allowing time for cutting and shaping (but omitting time for fitting to the wearer), each shoe would take about 2 hours to make, thus 4 labor hours for the pair.

Cloak – The cloak is straightforward, since it is simply a rectangular piece of woven cloth needing no sewing beyond the finishing of the edges. If the fabric was woven at a width of 1 meter, the selvages would make the long sides of the cloak; only the short sides would require hemming. At a hand-sewing speed of 1 meter per hour, sewing the cloak would take 2 labor hours.

Total cutting, sewing, and finishing time: 21 labor hours.

Fabrics/leather

Many factors affect the speed at which woven cloth is produced, from the size of the loom to the skill of the weaver. Historical recreations yield a range of weaving speeds from 180 to 255 square cm per hour. For the purposes of our project, we use an estimate of 200 square cm per hour for all types of fabric.

Linen – We need 1.575 square meters of woven linen, or 15,750 square cm, which would take approximately 79 hours to weave. Allowing time for set-up and maintenance of the loom and other necessary by-work, the production of the linen fabric from thread would require around 90 labor hours.

Silk – The calculations are similar for our silk. Weaving 2.025 square meters of silk would take a bit over 101 hours. With additional by-work, we can estimate about 110 labor hours to produce the silk fabric.

Wool – Likewise for our wool, the 2 square meters of wool we need would take about 100 hours to weave, coming to around 110 labor hours with additional work.

The time that it takes to spin the thread needed for weaving depends on how much thread goes into the finished fabric, which is affected by a host of factors: the thickness of the thread, the density of the weave, the width and length of the fabric, and so on. Rather than try to calculate all these possible elements, we work with a rough estimate that each of our fabric pieces required 10 km of thread, a measure based on both modern textile production and historical reconstructions. The further thread needed for sewing is a negligible addition. This rough figure allows for the possibility of variations in how each individual textile was produced while still giving us a reasonable estimate for the total investment of labor.

Spinning by hand yields around 40 to 60 meters of thread per hour. Taking the average of 50 m per hour, the 30,000 meters of linen, silk, and wool thread needed for our three pieces of fabric would take some 600 labor hours to spin.

Dyeing is a further step in the production process. The amount of time it takes to dye cloth depends on what dyestuffs are used, what kind of fabric is being dyed, and what the desired result is. Sourcing dyestuffs and preparing the dye bath also add to the labor. We estimate 10 hours of labor for each piece of fabric, and soaking in the dye bath adds several days of passive production time.

Leather – Leather production is complicated, as we outlined in our post about it. The two thirds of a square meter we need for our shoes could come from a single sheep hide (which typically yield 0.8 square meters of leather), but a lot of preparation and processing would have gone into making that hide into usable leather.

The amount of time it takes to produce leather from a fresh hide is widely variable depending on how the hide is treated and what steps are desirable for finishing it. Much of the time that it takes to prepare leather is passive time, as the hide sits on a rack or in various liquid treatments. For our purposes, we estimate that producing the leather for the shoes took 30 days from beginning to end, during which there were 12 hours of active labor. The passive production time for the leather can overlap with the passive dyeing time.

Total textile and leather production time: 952 labor hours, 30 days passive production.

Raw materials

We are estimating 10 km of thread of each fiber type for our complete outfit, but we must make a further calculation to determine how much raw material went into producing that thread. Threads can be spun at different thicknesses, so to get a sense of how much raw material went into our threads we need to convert length into weight. This conversion is expressed in a unit called tex, which gives the weight in grams of 1,000 m of a thread or yarn. Thinner threads are suitable for finer fabrics, while thicker threads can produce bulkier, rougher textiles. We consulted historical reconstructions to assign texes to our different threads.

Linen – For the linen undergarment, we want a fine fabric that feels good against the skin. For this purpose, we use a tex of 55, which means the 10 km of thread weighs 550 g. To get 550 g of spun linen thread we have to start with a much larger amount of flax, since flax processing removes as much as 90% of the material gathered from the field. Our 550 g of linen thread would require around 5.5 kg of flax.

Modern experiments with historical farming methods have yielded flax harvests of about 1 kg per square meter of field, so 5.5 kg of flax would need only about 5.5 square meters of field to grow in, which would take less than an hour both to plant and to harvest. Flax processing takes several steps, but for a modest amount of flax like this, the total active work time is not great. We can estimate 15 labor hours for flax processing from planting until the fiber is ready to spin. Along the way there is also about 100 days growing time for the plants, and some weeks passive time for retting.

Silk – For the silk tunic, we chose to use a coarser and heavier fabric with a tex of 180, which amounts to 1.8 kg in 10 km of thread. This amount of silk fiber represents the output of around 5,400 silkworms consuming the leaves of some 540 mulberry trees, which would need roughly 2 hectares of land to grow on. If starting silk cultivation from scratch, these trees would need a year to grow to maturity from the planting of cuttings, but we will assume that our silk comes from an established grove, and not count the planting, tree tending, or growing time into our estimates.

What we do need to account for, however, is the growth cycle and tending of the silkworms. Silkworms take 28 days from hatching until they are ready to spin, and require care as they grow. For our purposes, we estimate that caring for the silkworms takes at least eight hours of labor every day, between preparing food, feeding, and management. Once the cocoons are spun, a skilled hand can unreel their fiber quickly. Altogether, we estimate that the production of silk fiber takes 225 labor hours and 28 days of passive production.

Wool – Our wool cloak is a sturdy outer garment meant for warmth and protection against the elements. For this purpose we choose a tex of 500, which makes for 5 kg of wool thread. Historic breeds of sheep yield between 1 and 1.5 kg of wool per shearing, and some of that weight is lost in processing. We estimate that one sheep could yield 0.5 kg of wool fiber fit for spinning, so the 5 kg of fiber needed for our cloak represents one year’s fleece from 10 sheep.

A flock of 10 sheep would need some 10 hectares of grazing land. Sheep are sturdy animals and fairly self-reliant, but they do need tending to keep them safe from hazards and fed during the winter. We are being optimistic (perhaps even unrealistically so) and estimating 100 labor hours for sheep tending in a year. Once the fleece has grown, shearing is quick for a practiced hand. Based on various numbers given by modern shearers using hand shears, we estimate that a skilled shearer would be able to shear our 10 sheep in two hours. For the needs of wool production, then, we count 102 labor hours, a year of passive production, and 10 hectares of land.

Leather – The leather for our shoes could come from one of the sheep in the flock. Since the labor for tending the sheep is already accounted for, and slaughter and skinning are quick processes for an experienced hand, we add only 1 more labor hour to account for the production of the hide for tanning.

Total raw material production time and land needs: 343 labor hours, 1 year passive production, 12 hectares of agricultural and grazing land.

Final calculations

As we have noted many times, a lot of our figures are rough estimates at best. The actual production time for an outfit like ours would depend on numerous real-world factors that are beyond the scope of our project to account for. We are also largely discounting the effects of loss, wastage, and natural or human disaster—a flooded flax field or a neighboring people’s raid on the sheep pastures would throw all our calculations into disarray. Nevertheless, here is a rudimentary good-faith estimate of the time and land investment involved in making a single set of clothes in pre-modern conditions:

Active working time: 1,316 labor hours

Passive time: 1 year

Land requirements: 12 hectares

1,316 labor hours represents over 164 full 8-hours days of work for one person. Some of the work could be shared among several people, but there is a limit to how much efficiency could be gained by division of labor—you can’t make sheep grow fleece faster by adding more shepherds, for instance.

Once raw fibers have been produced, it would take some 973 labor hours to turn those fibers into finished clothes, or nearly 122 full 8-hour days. Even with a worker dedicated full-time to each material type (wool, linen, silk, leather), it would still take more than a month to finish the whole ensemble.

For one outfit, for one person to wear.

Furthermore, every labor hour devoted to clothing production was an hour of labor not available to produce food, construct or maintain buildings, care for children or elders, or engage in other activities that were necessary for the safety and well-being of a community. Clothing was not just something to wear for historical people; it was a statement about the prosperity of their own families and the communities they lived within.

Further Reading

Ejstrud, Bo (ed.). From Flax to Linen: Experiments with Flax at Ribe Viking Centre. Esbjerg: Ribe Viking Centre and University of Southern Denmark, 2011. https://ribevikingecenter.dk/media/10424/Flaxreport.pdf

Köhler, Carl. A History of Costume. New York: Dover, 1963.

Mallory, J. P. & Victor H. Mair. The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Mannering, Ulla & Charlotte Rimstad. Fashioning the Viking Age 2: From Analysis to Reconstruction. Copenhagen: The National Museum of Denmark, 2023. https://natmus.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Editor/natmus/oldtiden/Fashioning_the_Viking_Age/From_Analysis_to_Reconstruction_-_high_resolution.pdf

Owen-Crocker, Gale R. Dress in Anglo-Saxon England [revised and enlarged ed.]. Woolbridge: Boydell Press, 2004.

Pasanen, Mervi & Jenni Sahramaa. Löydöstä muinaispuvuksi [From Finds to Reconstructed Dress]. Salakirjat, 2021.

Postrel, Virginia. The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

Strand, Eva Andersson & Ida Demant. Fashioning the Viking Age 1: Fibres, Tools & Textiles. Copenhagen: The National Museum of Denmark, 2023. https://natmus.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Editor/natmus/oldtiden/Fashioning_the_Viking_Age/Fibres__Tools_and_Textiles_-_high_resolution.pdf

Walton Rogers, Penelope. Textile production at 16-22 Coppergate. York: Council for British Archaeology, 1997. https://www.aslab.co.uk/app/download/13765738/ASLab+PWR+1997+AY17-11+Textile+Production+for+web.pdf

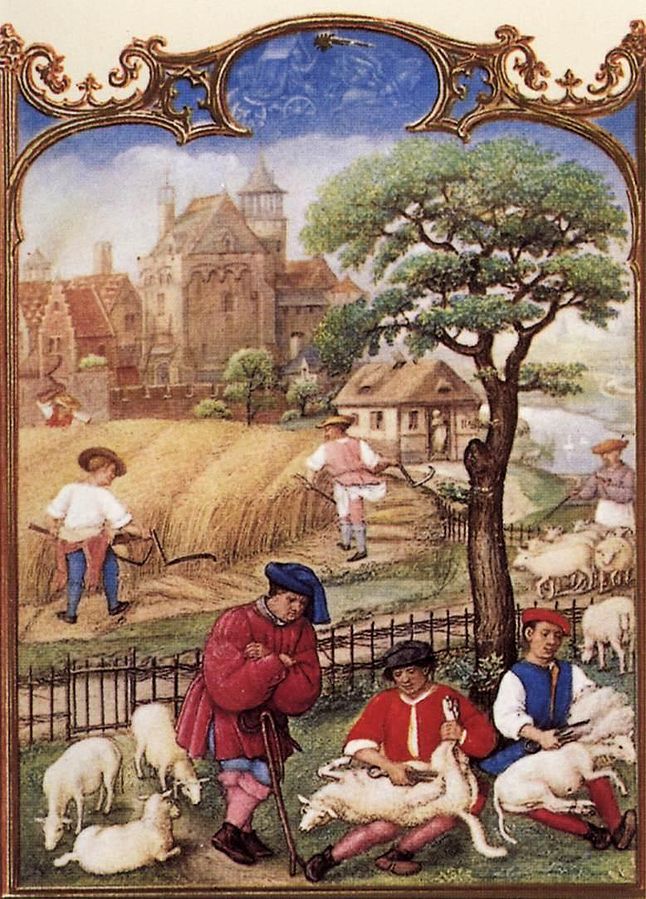

Images: Medieval man via Jo Justino at Pixabay. Sample T-tunics by Eppu Jensen. Hand-stitching leather shoes, photograph by Jeff Mandel via ExIT Shoes (CC BY 4.0). Spinning and dyeing in Chinchero, Peru, by Shawn Harquail via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0). July, from the Grimani Breviary via Wikimedia (Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana; 1490-1510; illumination on parchment). Small Herculaneum Woman, reconstruction of a marble statue, by Billy Wilson via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

How It Happens looks at the inner workings of various creative efforts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.