Monday is when I write, from a historian’s perspective, about some interesting or useful tidbit for writers, especially writers of genre fiction. I’m doing that again today, but from a different angle. Today I want to talk about representation, specifically the representation of people who are not straight white cis men in books, television, movies, games, and other media.

First things first: I’m a straight white cis man with no significant mental or physical challenges. I am a native-born citizen of the country in which I live and a native speaker of its majority language. I am financially secure and socially comfortable. I am not, as far as I know, heir to any titles of nobility, but other than that, if a privilege exists in the world, I’ve probably got it.

Yeah. I’m about to talk about representation. If anyone wants to get off this ride, now’s the time.

When creators and fans talk about adding representation to popular media, the refrain from people who look like me is often: “Why do we have to have X in this story? What do you mean you can’t identify with the characters? Why can’t all you Xes identify with people who aren’t exactly like yourselves?”

I understand where this response comes from. There are white guys all over the place in popular media, but I’ve never identified with a character just because he was a white guy. There are so many of them that I couldn’t identify with them all if I wanted to. When I look at a character and think Hey! That’s me! it comes from traits other than outward identities. Here are some of the characters I’ve felt connected to over the years:

They’re not all the same gender, race, age, or even species as I am. Two of them are members of a religious order, and I’m not religious at all. Most of them don’t even (fictionally) live in this century.

What can we learn from this collection? (Other than that I have a thing for Vulcans and a rather inflated sense of my ability to dole out wise advice to young ‘uns.) That representation is an aspect of privilege even when you’re not being represented. Having white guys all over the place frees me to look at the characters in my media and identify with them not based on the outward categories they fall into but because they’re thoughtful, introverted, curious, even-tempered, and passionate about knowledge.

On the other hand, I am a member of a very small minority who is rarely represented in media, and then usually in a dismissive, stereotyped, even offensive way: history professors. According to most books, movies, and tv shows, we are boring, joyless pedants in tweed jackets with elbow patches who obsess over minutiae and care only about names and dates.

“Easily the most boring class was History of Magic, which was the only one taught by a ghost. Professor Binns had been very old indeed when he fell asleep in front of the staff room fire and got up the next morning to teach, and left his body behind him. Binns droned on and on while they scribbled down names and dates, and got Emeric the Evil and Uric the Oddball mixed up.”

– J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s / Sorcerer’s Stone Ch. 8

We always wear period clothes and are at best dimly aware of what century we actually live in, if not actively in denial about it.

(Not to mention that we make our (black) graduate students do unpaid labor so that they can have the “authentic slave experience.”)

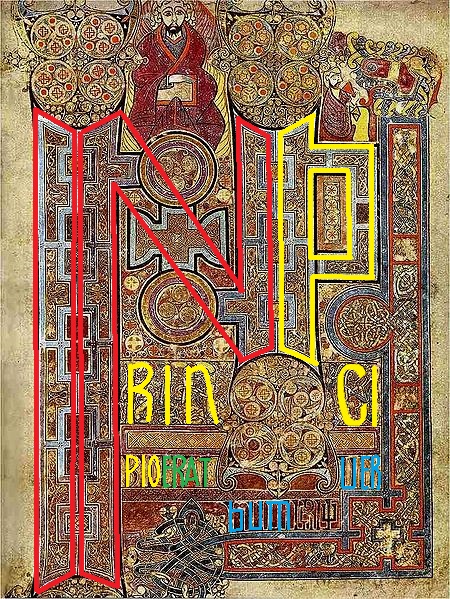

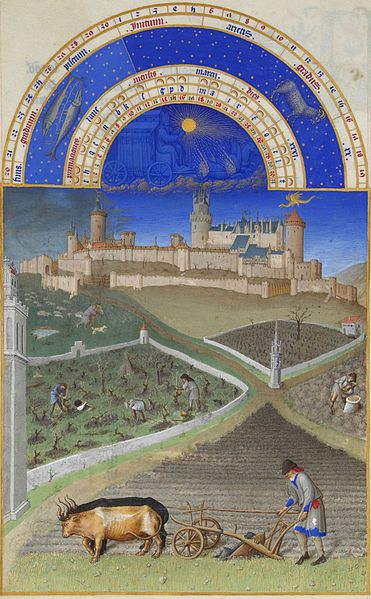

Oh, and if we’re medieval historians, we’re indistinguishable from renfaire performers. (I can’t find a link to it now, but the memory is seared in my mind of an NPR interview with a scholar attending the annual medieval studies conference in Kalamazoo which made it clear the interviewer thought it was basically a fantasy convention.)

Come on by my history class sometime. I won’t be wearing a costume or droning on about names and dates. I’ll be deep in conversation with my students about social structures, economic forces, multicultrual interactions, source analysis, and all the other interesting parts of history.

Now, history professors are not, by any stretch of the imagination, a historically oppressed or marginalized group. I know how aggravating it can be to be badly represented even as a comfortably privileged middle class white man, but I can’t really imagine what it must be like to be, say, a Native American woman, or a gay man who uses a wheelchair, or a Muslim teenager with Asperger’s, and have to deal with not only the weight of the social disadvantages that come with that and seeing people like myself so rarely and poorly portrayed in media.

Of course we can all identify with people who aren’t like us. That’s not the point. The point is that, no matter who we are, we all deserve to see enough people outwardly like ourselves in books, television, movies, and other media that we don’t have to identify with them just to feel like we’re there.

Images: Spock via Memory Alpha; Guinan via Memory Alpha; Cadfael via Heroes Wikia; Minerva MacGonagall via Harry Potter Wiki; Gil Grissom via CSI: Wiki; Sister Monica Joan via PBS; Mr. Bennet via Jane Austen variations; Cora Crawley via Downton Abbey Wiki; Tuvok via Wikimedia; Rizzoli and Isles “Rebel Without a Pause” via Sidereel

History for Writers is a weekly feature which looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool. From worldbuilding to dialogue, history helps you write. Check out the introduction to History for Writers here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.