It’s an all too well-known trope that the past is drab. When we picture ancient or medieval buildings, we tend to imagine white marble or gray stone. This assumption of colorlessness spills over into fantasy as well. When we imagine the built environments of made-up lands, we tend to see a lot of white and gray there too, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus gives a fantastical description of the Median city of Ecbatana, modern Hamadan, Iran, featuring a series of concentric walls topped by brightly colored parapets:

This walled city is built in such a way that each wall is higher than the wall encircling it by only the height of its parapet, partly by the fact that it is built on a hill, but largely by design. All together there are seven circles, with the palace and treasury in the innermost one. The largest wall is about as long as the walls of Athens. The parapet of the first wall is white, the second one black, the third red, the fourth dark blue, and the fifth amber. The first five walls had their parapets painted in these bright colors, but the next was covered in silver and the final one in gold.

– Herodotus, Histories 1.98

(My own translation)

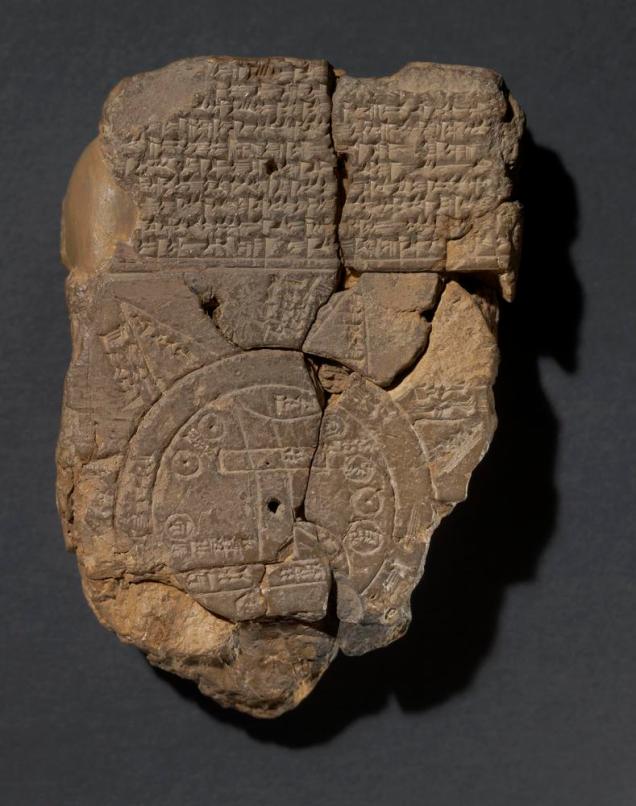

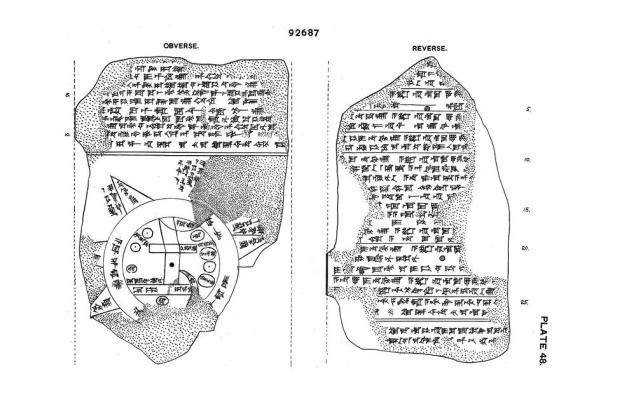

Now, Herodotus probably got this description wrong. It does not match up with the archaeological remains on the ground in Hamadan. Herodotus never saw Ecbatana for himself, but relied on second-hand reports, which likely got garbled in the telling. In fact, Herodotus’ description of Ecbatana as a hill covered by concentric rings of walls fits a bit better as a description of a Mesopotamian ziggurat. A ziggurat is a pyramid-like structure made up of a series of terraces built one on top of another, getting smaller as they go up. Seen from ground level, they might well look like a series of concentric walls ascending a hill.

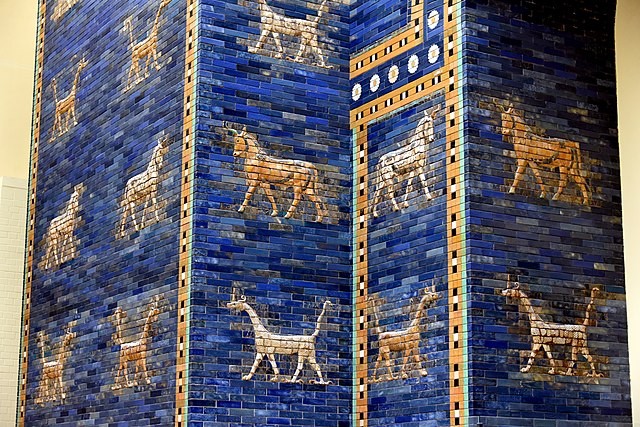

Ziggurats had been built in Mesopotamia for thousands of years by Herodotus’ day, primarily to serve as temples. While not many new ziggurats were being built in the time of Herodotus, older ones were being restored and rebuilt, so news of a freshly (re)built massive structure with impressive concentric walls may well have reached Greece. The brightly colored walls Herodotus describes are not too far-fetched, either. Ancient Mesopotamians decorated important buildings with colorful glazed tiles, which still retain some of their impressive coloring even today, as can be seen in the Ishtar Gate from Babylon.

All of these things put together mean that Herodotus invented (albeit unintentionally) a fantasy version of Ecbatana flavored after a Mesopotamian ziggurat with colorful tiled walls. And if Herodotus could do it, there’s no reason the rest of us can’t do the same. Let’s see more fantasy cities with vibrant scarlet walls, turquoise roof tiles, or streets paved with lush green stone!

History for Writers looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool, from worldbuilding to dialogue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.