There is little we can say for sure about the life of Doricha (sixth century BCE, approximately contemporary with the poet Sappho). Most of what we know about her comes from legends and tales that make her larger than life. Even so, those legends in themselves tell us something important about the world of the Mediterranean in the Greek archaic age.

Doricha was a courtesan (hetaira in Greek) who worked in the city of Naucratis in Egypt. Courtesans were a class of sex workers in the ancient world, but unlike lower classes of sex workers, who provided sexual services in return for fairly standard rates of pay, courtesans offered and expected much more. A courtesan would do more than have sex with a client (although that was part of what she offered); she offered companionship, conversation, artistic performance, and social grace. What she received in return was often not so clearly specified. It could include money, but also gifts of jewelry, clothing, furniture, and food. She might enjoy a house paid for by a client, or even live with him long term. Courtesans often had ongoing relationships with a select few clients, and part of their work was to build the illusion of a purely romantic and emotional relationship around what was at base an economic transaction of pay for services. This was demanding work, and not everyone could do it well. A successful courtesan had to cultivate an aura of mystery and glamour. At the same time, courtesans were exposed to all the same pressures and dangers that women offering sex in exchange for money have always faced in male-dominated societies. Yet for some women, those who were lucky and who were good at their jobs, work as a courtesan offered a path to personal independence and financial security that few other women in the Greek world could claim.

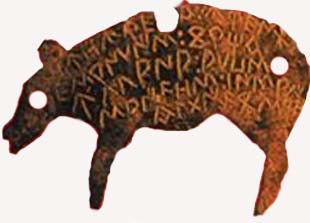

Doricha was both lucky and good at her job. Originally from Thrace, she arrived in Naucratis as a slave being put to sex work by her owner, a Greek merchant from Samos named Xanthes. While working in Naucratis, she met Charaxus, brother of the poet Sappho, who was trading wine from the family’s home on Lesbos to Egypt. Charaxus was so smitten with Doricha that he bought her freedom from Xanthes. (When he got home, Sappho had some choice things to say about how he had spent the family’s hard-earned money on his business trip, bits of which survive in some of the fragments of her poems.) She then chose to remain in Naucratis and keep working as a free woman the trade she had begun as a slave. She became so successful that at the end of her life she wanted to leave a lasting memorial of her wealth. According to a story told by Herodotus, she spent one tenth of her fortune to make a massive pile of iron roasting spits and deposited them at Delphi, the site of the famous oracle, where Herodotus reports that they were still to be seen in his day. (Herodotus, Histories 2.135)

Like other courtesans, she cultivated an intriguing persona to appeal to her clients. This persona included an alias, Rhodopis, meaning rosy-cheeked in Greek, by which name she is better known. (It was not unusual for ancient courtesans to use aliases, for all the same reasons that women today performing as strippers or porn stars do.) This mysterious persona influenced how her life was told and retold in later generations, and a number of folktales became attached to her story. One claims that while she was a slave in Samos, the fable-writer Aesop was at the same time a slave in the same household. While this one is not impossible, the coincidence stretches belief (and it is not even certain among scholars today that Aesop was ever a real person). Other stories are attached to Doricha’s later life and are even more unbelievable.

One popular tale is the earliest known version of the Cinderella story:

They say that one day, when Rhodopis was bathing, an eagle snatched her sandal from her serving maid and carried it away to Memphis. There the king was administering justice in the open air and the eagle, flying over his head, dropped the sandal in his lap. The king, moved by the beauty of the sandal and the extraordinary nature of the event, sent all through the country to find out whose it was. She was found in Naucratis and conducted to the king, who made her his wife.

– Strabo, Geography 17.1.33

(My own translation)

Another popular myth among Greeks held that one of the three great pyramids at Giza was Doricha’s tomb, built for her by the king after her death. (Herodotus correctly points out that this story was impossible as the pyramid actually belonged to the king Mycerinus, who ruled Egypt some two thousand years before Doricha ever got there, but he also documents that it was a tale widely known among Greeks. Herodotus 2.134) Doricha’s life was one that seemed fabulous, bordering on the mythic. Some of that wonder is down to Doricha herself, who certainly seems like she would have been an interesting person to know, but the tales about Doricha also reflect the wider Greek experience in Naucratis.

In Doricha’s day, Naucratis was a newly-founded Greek colony, and a unique one. Over the course of the archaic age (roughly 750-480 BCE), Greek cities founded numerous colonies around the shores of the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Some of these colonies were large settlements devoted to controlling farmland and producing food, which was a scarce resource back home in Greece, and some colonies either began with or in time acquired a military might that was able to dominate and subjugate the local peoples, but not all colonies were of that kind. Many were small, fairly humble trading posts or Greek immigrant neighborhoods already busy foreign cities and ports. In these colonies, good relations with local people as hosts and trading partners were essential. Naucratis was in some respects like these trading colonies, and one of its important functions was as the official port of trade for Greeks in Egypt. (Herodotus 2.178-9)

Naucratis was also different. It was the only foreign settlement in Egypt officially sanctioned by indigenous kings, and it had begun not as a trading post but as a settlement of Greek and Carian mercenaries in Egyptian service. The kings of Egypt found the Aegean world to be useful recruiting ground for professional soldiers. Greece had all the qualities that powerful states have historically looked for to find mercenaries: it was poor, politically disorganized, and wracked by violence. The result was a large population of experienced fighters who had no stable home or livelihood. Naucratis became not only a place where Greek merchants could bring goods that were in demand in Egypt, like iron, wine, and olive oil, but also a place where Greek soldiers who fell on hard times could go to find ready employment in the Egyptian army.

For the Greeks, Naucratis was the gateway to Egypt and to the possibility of striking it rich, whether as a courtesan, merchant, or mercenary. The tales told about Doricha reflect this sense that Naucratis was a place where amazing things could happen, where one could imagine starting out as a slave and ending up the rich and beloved consort of the king. Most people who came to Naucratis, of course, never had such success, but Doricha is evidence of what was possible there for the talented and lucky. While her story may have been exaggerated over time, it is clear that she managed an enviable rise from low status to exceptional wealth.

Opportunities of this kind were available in the Greek colonies for those lucky enough and determined enough to make the most of them, but making it big in a place like Naucratis required one skill above all: the ability to work across cultural boundaries. Doricha was originally from Thrace. She made her name by serving Greek merchants in Egypt, and at the end of her life she proudly proclaimed her success by making a dedication in the international sanctuary at Delphi, a place frequented not only Greeks but by people of many cultures around the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. The legends about her life imagine her becoming the beloved of the Egyptian king and being commemorated with an Egyptian tomb. All of the other merchants and mercenaries who sought their fortune in Naucratis had to negotiate similar boundaries. Doricha’s life is an example of what could be achieved by those who mastered the art of cosmopolitanism.

Image: “The Beautiful Rhodope in Love with Aesop” via Wikimedia (1780; engraving by Bartolozzi after a painting by Angelica Kauffman)

History for Writers looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool. From worldbuilding to dialogue, history helps you write.

You must be logged in to post a comment.