The word “barbarian” today conjures a fairly specific image: a large, muscular man or woman wearing leather or furs hefting an enormous weapon. They are ragged and dirty and if they have any kind of organization, it is as a rabble of warriors following whoever happens to be the strongest. This image has its roots in classical Greek and Roman literature, but Greco-Roman ideas about barbarians were broader and more complicated than this.

The word “barbarian” today conjures a fairly specific image: a large, muscular man or woman wearing leather or furs hefting an enormous weapon. They are ragged and dirty and if they have any kind of organization, it is as a rabble of warriors following whoever happens to be the strongest. This image has its roots in classical Greek and Roman literature, but Greco-Roman ideas about barbarians were broader and more complicated than this.

Greeks and Romans both had complicated relationships with the outside world. The economy of ancient Greece depended on foreign trade, especially with Egypt, but Greece was also on the northwestern frontier of the Persian empire, which often threatened Greek cities or interfered in their internal politics. Rome was an expansionist empire with ambitions of conquering the whole world, but the strength and stability of the empire depended on integrating conquered peoples into Roman culture.

Out of these historical experiences, Greek and Roman writers, artists, and philosophers developed a wide repertoire of narrative models for describing other peoples. These narratives ranged from the nuanced and admiring to the stereotyping and pejorative. “Barbarian” could mean many different things in different times and contexts. Among this repertoire, there were conventional archetypes that authors and artists could draw on and expect that their audience would recognize them.

These archetypes were nebulous conglomerations of tropes and stereotypes, not always consistent and liable to be manipulated, tweaked, and subverted in individual works of art or literature. They could be reduced to caricature or filled out with individual details. They functioned much like modern national and ethnic stereotypes. Imagine the caricature version of a British gentleman, replete with bowler hat and umbrella. We might expect such a character to have certain typical qualities, both positive (unflappable, chivalrous, witty) and negative (stodgy, proud, insensitive) and engage in typical behaviors (sipping tea, playing polo, driving a Jaguar). Of course, stereotypes don’t have to be followed. A Brit in a bowler hat with an umbrella may also turn out to be a tongue-tied chocoholic who raises miniature goats and likes to watch telenovelas, but the author who creates such a character and the audience that encounters them will recognize how the standard tropes have been played with.

Greeks and Romans had two principal archetypes for barbarians. One was based on small, materially poor, less well organized cultures mostly found to the west or north, such as Scythians, Thracians, Gauls, Germans, Iberians, Britons, and Dacians. The other was based on large, wealthy, sophisticated cultures mostly found to the east or south, such as Egyptians, Persians, Phoenicians, Lydians, Carthaginians, and Etruscans.

The northwestern barbarians are the ancestors of the modern “barbarian” image. They were portrayed as violent, ignorant, savage, and lacking in technology and social organization. They had no idea how to behave in a civilized society and were almost like wild animals. They lived in poverty and with barely any kind of government except the ability of the strong to impose their will on others. They could also be shown with good qualities, such as generosity and honesty. The were the original “noble savages,” ignorant of the benefits of civilization but also uncorrupted by its temptations.

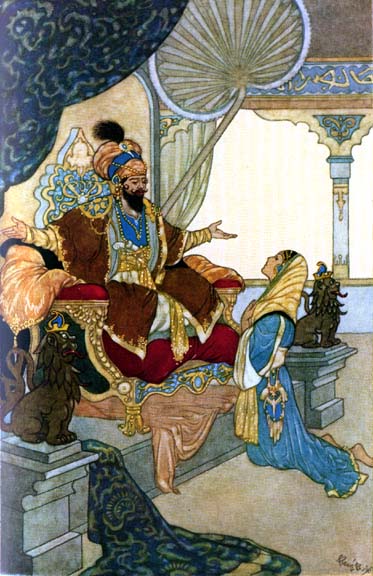

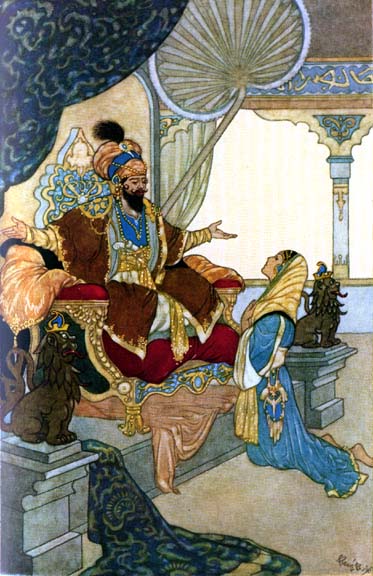

The southeastern barbarians were the opposite. They were portrayed as weak, decadent, devious, overwhelmed by luxury and tangled in arcane social hierarchies. They had given in to the corrupting effects of civilization and overindulged in every kind of physical pleasure. They lived like slaves under the rule of despotic tyrants, but they were so accustomed to the comforts of luxury that they lacked the will to resist. They could have positive qualities as well. Their cultures were ancient and sophisticated, rich in accumulated knowledge. We don’t have a good term for the opposite of “noble savages,” but we might call them “depraved sophisticates.”

The southeastern barbarians were the opposite. They were portrayed as weak, decadent, devious, overwhelmed by luxury and tangled in arcane social hierarchies. They had given in to the corrupting effects of civilization and overindulged in every kind of physical pleasure. They lived like slaves under the rule of despotic tyrants, but they were so accustomed to the comforts of luxury that they lacked the will to resist. They could have positive qualities as well. Their cultures were ancient and sophisticated, rich in accumulated knowledge. We don’t have a good term for the opposite of “noble savages,” but we might call them “depraved sophisticates.”

Central to both of these archetypes is one of the key values of Greco-Roman society: self-control. The southeastern barbarians displayed too little of it, giving in every kind of indulgence and unable to resist the rule of a tyrant. The northwestern barbarians, by contrast, were too willful, unable to subordinate themselves to the structures of law and social order. By creating these archetypes, Greeks and Romans positioned themselves in the middle—sophisticated enough to enjoy the benefits of civilization, but strong enough to resist its corrupting effects.

Both of these archetypes have come down into modern literature. The northwestern barbarian has become the standard modern “barbarian,” but aspects of it can also be seen in modern Western stereotypes of Africans, African Americans, and Native Americans. “Darkest Africa” stories about wild cannibal tribes dumbfounded by modern technology and scientific knowledge play upon the same images of violence, savagery, and technological ignorance that Romans applied to the Gauls and Germans. The southeastern barbarian formed the basis for romanticized Western depictions of the Islamic world, China, and India. “Arabian Nights” fantasies of scandalous harems and treacherous palace politics, ancient secrets and fabulous treasures hidden in the twisting back streets behind markets filled with spices and gems evoke Greek tales about Egypt and Persia.

These archetypes have also found their way into fantasy and science fiction. Tolkien’s Elves reflect some of the more positive southeastern qualities of wisdom and sophistication while his Orcs display the violent, fractious, bestial traits of the northwest. Star Trek‘s Klingons and Romulans represent the tropes of warlike honor and treacherous sophistication. The people of Westeros in A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones face the rugged, wild, disorderly peoples of the north and the rich, old, devious kingdoms of the east.

Once you know your barbarians, you’ll recognize them everywhere.

Images: Hyboria, by Yan R. via Flickr. Sultan from the Arabian Nights, by Rene Bull via Wikimedia.

History for Writers is a weekly feature which looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool. From worldbuilding to dialogue, history helps you write. Check out the introduction to History for Writers here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.