(Read previous entries here and here.)

(Read previous entries here and here.)

So far, it’s going okay. I have started posting introductions and discussion questions for the blocks of content that my students will be covering for the rest of the spring. Across all my classes, there will be a total of twelve blocks for students to read and respond to. Prepping one block takes me about two solid days of work. I have posted five so far, with seven left to go. Allowing time for housework, fresh air, cooking, and other essential things, I’m probably looking at between two and three weeks more of work to get everything online. Then I’ll be spending the rest of April grading assignments as they come in and keeping an eye of the discussion forums.

Students have started engaging in discussion already. Only a few so far, but that’s understandable. I know everyone is busy right now and it’s going to take people time to get used to new ways of doing things. Responses have been productive. Students are engaging with the ideas I want them to engage with and showing that they have done the new readings and can relate them to ideas we discussed earlier in the semester. That’s as much as I feel I can ask of them right now.

I’m holding virtual meetings with my classes this week via Zoom (videoconferencing service). Not to teach anything new, just to check in with them, go over the procedure for the rest of the semester, and answer their questions. I’ve let everyone know that these meetings are entirely optional, and there will be no negative consequences if they don’t join in. I hope a lot of them will show anyway. I miss seeing them, and I’d like to know that they’re okay.

The big question hanging over all of this is: what will happen to this semester’s grades? As I mentioned last time, the university administration is considering the possibility of shifting to a pass/fail system for this semester, or of giving students the option to individually take courses as pass/fail. Nothing is certain yet, but clarity will hopefully come soon. I’m divided on whether I think it’s a good idea or not. On one hand, there is no way to treat this semester like an ordinary spring or to imagine that the grades students get at the end of it are really comparable to their grades form other semesters. A lot of my students are in difficult situations right now, and going pass/fail might take a burden off their shoulders. On the other hand, implementing such a big change on the fly is going to be a mess, and I worry about people falling through the cracks in a system that none of us have had time to think through and shake the bugs out of.

You see, the secret truth about teaching is: grades mean nothing. Or at least nothing much. A grade is never anything more than your professor’s best attempt to convey to you how well they think you have understood what they were trying to get you to see, and there is no objective way of measuring that. Even in disciplines that have clear right and wrong answers, the decision about what questions to ask is still fraught with human subjectivity. Good and conscientious professors will try to use their grades as a way of communicating honestly with you about what you have accomplished during your time in their class, but the whole thing is an eggshell balanced on top of a rickety shack built on quicksand. You don’t have to stir the sand much before everything breaks.

Let’s hope we don’t break things too badly and we can find a way of doing right by our students.

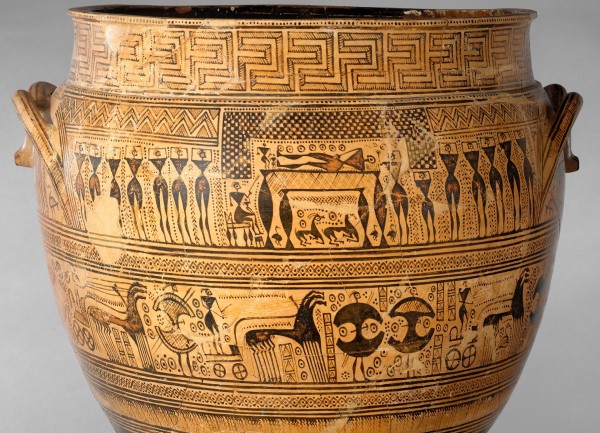

Image by Erik Jensen

How It Happens is an occasional feature looking at the inner workings of various creative efforts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.