The religions that exist in our world can be broadly divided into two categories: traditional religions, which developed gradually in their own native societies and have no clear beginning point, and novel religions, which began at a fixed point in time. Many of the great world religions of the modern day, like Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, are novel religions, while some traditional religions, like Shinto, still thrive. Some religions, like Hinduism and Judaism, have features of both. In earlier posts, we’ve discussed what sort of things you may want to keep in mind in your worldbuilding for stories or games to make your imaginary religions feel more authentically traditional. Today we’ll take a look at what makes a novel religion feel alive.

The religions that exist in our world can be broadly divided into two categories: traditional religions, which developed gradually in their own native societies and have no clear beginning point, and novel religions, which began at a fixed point in time. Many of the great world religions of the modern day, like Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, are novel religions, while some traditional religions, like Shinto, still thrive. Some religions, like Hinduism and Judaism, have features of both. In earlier posts, we’ve discussed what sort of things you may want to keep in mind in your worldbuilding for stories or games to make your imaginary religions feel more authentically traditional. Today we’ll take a look at what makes a novel religion feel alive.

There have been many novel religions in world history. A few have gathered large followings and become major forces in the world. Many have faded away after a few generations. Some have done well for a long time, even for centuries, before finally disappearing. There is no single thing that every novel religion has in common, but looking at history, we can see definite patterns as to what makes a new religious movement thrive, even if only for a time. It takes more than a charismatic leader with a new idea, although that is where most of them start.

Connection to the past

New ways of life can be hard to adopt, but they are easier if they connect to things people already know. Christianity and Islam both drew on Jewish traditions, as Buddhism did with the same ancient Indian traditions that informed Hinduism. The ancient Mediterranean cult of Isis based itself on ancient Egyptian religion. Similarly, Zoroastrianism drew on ancient Iranian religious ideas. New movements within existing religions that do not split off on their own also often share the features of novel religions, like the Protestant denominations within Christianity or the Shia branch of Islam. The degree to which new religious movements identify themselves as new or as reforms to or revivals of older traditions can vary widely.

Texts and beliefs

Not every religion, novel or traditional, has sacred texts, but many novel religions do. Such texts help to define how the new movement differs from what has come before and what its followers are expected to do or believe in order to be counted as part of the group. Depending on the religion, these texts may be openly available to anyone who wants to read them, or access to them may be limited only to those who have joined the movement. Novel religions are also more likely to focus on belief, unlike traditional religions which tend to focus on practices and rituals.

Hope in times of trouble

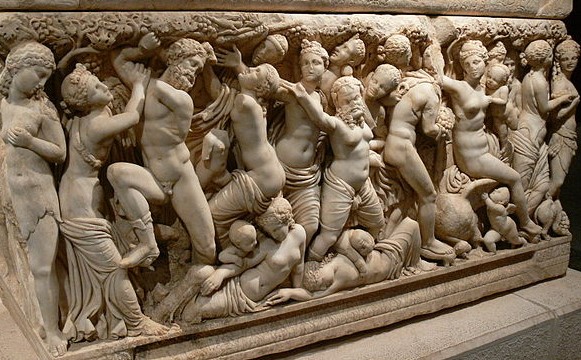

The success of any new religion depends largely on its ability to attract new followers in sufficient numbers to keep the movement going. Most people most of the time aren’t really “in the market” for a new religion, but there are certain times in history when large numbers of people are ready to embrace something new. It tends to happen in times of suffering and uncertainty, among people who have been displaced from their homes and familiar ways of life. The Bacchanal cult of the second century BCE appealed to Italian peasants who had been driven from the countryside into the cities by economic desperation. Haitian Vodou and related religions came out of the traumas of enslaved West Africans in the Caribbean and the Americas. Christianity and Islam both, in different periods and different ways, emerged among the victims of Roman imperialism. Novel religions often offer purpose, identity, and community to people who have lost the things that gave them those comforts before.

Difficult (but not too difficult)

A novel religion often thrives when it demands practices of its followers that are difficult, but not excessively difficult, to carry out. Muslims are expected to pray five times a day. Buddhists engage in meditation of many different kinds. Followers of Isis were expected to furnish a feast for their fellow worshipers upon joining. These kinds of practices, which require time, focus, and effort, but are not overly demanding, help foster a sense of community by creating shared experiences. At the same time, religions which demand overly difficult practices tend to see their followings dwindle. Converts to Mithraism went through initiations involving withstanding heat, cold, and pain (although probably not bathing in bull’s blood, as sometimes alleged). The rigors of these initiations, as well as the fact that it seems to have been open only to men, may have limited the cult’s appeal and kept it from gaining a critical mass of followers.

Outward from the middle

Novel religions tend to begin neither at the top nor at the bottom of the social scale but somewhere in the middle. Simply put, the rich and powerful have little to gain from upending the order of things, while the poor and powerless don’t have the time to ponder on the mysteries of the universe. New religious movements tend to begin among people who, if not always “middle class” by a modern definition, are somewhere on the middling ranks of the social and economic hierarchy. How they spread from there differs. Some religions grow by promising the hope of a better life to the poor, as Christianity did, while others, such as Confucianism, grow by appealing to a discontented elite.

Food

Food, for many of us, is a vital part of our sense of identity and community—think of your favorite family recipes or the special holiday dishes that remind you of heritage and home. Many novel religions present new ways of eating as part of the creation of a new communal identity. One of the central rituals of Christianity involves consuming (literally or metaphorically, depending on one’s theology) the body and blood of the founding figure. Muslims are enjoined to fast during daylight hours during Ramadan and to avoid certain food and drink, including pork and alcohol, altogether. Manichaeism taught that adherents had a duty to spread light in the world and combat darkness by eating certain foods and avoiding others. Eating together, or eating in similar ways to other followers elsewhere, helps to maintain the bonds that hold the adherents of a new religion together.

Thoughts for writers

As an example of how these features of novel religions can inform worldbuilding, here is a short description of an imaginary movement in an imaginary world.

The borderlands of Jash have been ravaged by decades of war between the Jashite cities and the invading armies of the Akluni Empire. As refugees from the rugged hills and scrublands of northern Jash stream into the cities of the lush Jash River valley, they find misery, poverty, and violence. Many of the refugees, looking for the solace of the familiar, have filled the neglected temples of Uzuli, the moon goddess favored by borderland shepherds but little regarded by the city folk.

Among the merchants and farmers of the Jash cities, tensions have been growing as no city seems capable of leading a coordinated response to the Akluni threat. Factions have formed within the cities, some arguing for peace with Aklun, others for resistance to the death; some for throwing the refugees out to fend for themselves, others for redistributing farmland to provide for the hungry. Encounters between members of these factions in the streets and market often lead to harangues, arguments, even fistfights.

Lately, a woman calling herself the Moon Daughter has been gathering crowds in the side streets of the city of Busa, giving stirring speeches promising a return of peace and prosperity. She comes from one of the lesser merchant families of Busa, but no longer speaks to them after beginning her work in the streets. She reports visions from Uzuli that call for all the people of Jash to be as one, to return to the simpler ways of the country, and to withstand the assault of Aklun not by arms but with the patience of Uzuli, who does not fear the waning because she knows that the full moon will come again.

The Moon Daughter’s early followers came from among other merchants families, whose fortunes have fallen under the pressure of war, but she increasingly draws crowds of hinterland refugees. Some of her followers have begun writing down her speeches and publishing them as pamphlets. “Eat of the bitter terebinth and the prickly pear” she says, “in memory of our home that is lost. Then drink of the honeyed wine that promises peace and harmony forever in the turning of the moon.” Her followers gather for common meals, eating and drinking as she commands, but also sharing what food they have with those who have none.

Building in some of the common features of novel religions helps the Moon Daughter’s movement feel fuller and more grounded in the world. It also offers interesting storytelling hooks. What happens if Busa is conquered by Aklun and the Moon Daughter and her followers have to flee elsewhere? What if the priestesses of Uzuli challenge the Moon Daughter for false prophecy? What if the Moon Daughter’s movement becomes so popular its followers take control of Busa, and then have to negotiate with the other Jashite cities who haven’t joined the movement? What if the Akluni Empire collapses and the refugees return home bringing the Moon Daughter’s words and ideas with them, but leaving the life of the city far behind? There are lots of directions you could take a story or a game from this beginning.

Other entries in Fantasy Religions:

Image: Manichaean diagram of the universe via Wikimedia (China; 1279-1368 CE; paint and gold on silk)

History for Writers is a weekly feature which looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool. From worldbuilding to dialogue, history helps you write. Check out the introduction to History for Writers here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.