Hidden Youth comes out today! Among the many short stories in this collection about young people from marginalized groups in history is my story, “How I Saved Athens from the Stone Monsters,” about the adventures of two flute girls, one Egyptian and one Thracian, on one strange and terrifying night in ancient Athens. I hope you’ll consider picking up the collection, not just for my story but for all the other amazing work in it.

Hidden Youth comes out today! Among the many short stories in this collection about young people from marginalized groups in history is my story, “How I Saved Athens from the Stone Monsters,” about the adventures of two flute girls, one Egyptian and one Thracian, on one strange and terrifying night in ancient Athens. I hope you’ll consider picking up the collection, not just for my story but for all the other amazing work in it.

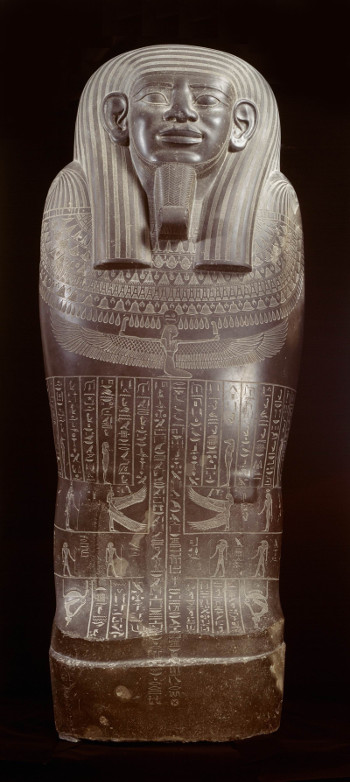

My story was inspired in part by the Egyptian and Thracian immigrant communities we know existed in Classical Athens. There were temples in the city to both the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Thracian goddess Bendis. But Athens wasn’t the only place Egyptians and Thracians crossed paths.

A famous Thracian courtesan named Rhodopis worked in Naucratis, the Greek trading city in Egypt in the 6th century BCE. She seems to have been a larger-than-life character whom people liked to tell stories about. It was apparently widely believed in antiquity that one of the three great pyramids at Giza was built for her by her lovers. Another fanciful story about her is the closest ancient equivalent to the story of Cinderella:

They say that one day, when Rhodopis was bathing, an eagle snatched her sandal from her serving maid and carried it away to Memphis. There the king was administering justice in the open air and the eagle, flying over his head, dropped the sandal in his lap. The king, moved by the beauty of the sandal and the extraordinary nature of the event, sent all through the country to find out whose it was. She was found in Naucratis and conducted to the king, who made her his wife.

– Strabo, Geography 17.1.33

(My own translation)

While this is obviously just a bit of a fairy tale, Rhodopis was a real person. One of her lovers was Charaxus, the brother of the lyric poet Sappho. Sappho evidently didn’t think much of the relationship. A fragment of one of Sappho’s poems throws a little shade the courtesan’s way (referring to Rhodopis as Doricha—it was not unusual for courtesans to use several different names):

O, Aphrodite, may she find you too bitter for her taste,

and don’t let her go boasting:

“What a sweet thing Doricha has got herself into

this time around!”

– Sappho, fragment from Oxyrhynchus papyrus 1231.1.1.(a)

(My own translation)

Herodotus reports that the rich offering Rhodopis made at Delphi at the end of her life to celebrate her good fortune—an enormous pile of iron roasting spits—was still to be seen there in his day. (Herodotus, Histories 2.135)

Rhodopis sounds like she would have been an interesting person to hang around with, and Hidden Youth is one more reminder that interesting people were everywhere in history, not just in the places we expect.

Image: Greek statue of Bendis, photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia (Cyprus, currently Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 3rd c. BCE; limestone)

Announcements from your hosts.

Recent archaeological work

Recent archaeological work

You must be logged in to post a comment.