This post is a part of our Making Clothes series.

Plant fibers come basically from one of three parts: stem, leaves, or seeds. Bast fibers are harvested from the stems of various plants or trees and include flax (linen), hemp, jute, and ramie (a nettle family plant). Among leaf-derived fibers, sisal is perhaps the most commonly known. Seed fibers include cotton, coir (coconut shell fiber), and kapok, for example.

Plant fibers have been used for textile production for tens of thousands of years, at latest since the Neolithic. Many of the coarser plant fibers were (and still are) used for utility items like ropes and cords, nets, sails, bags, sacks, packs, and various wrappings. The softer ones were, naturally, a desireable material for wearable textiles.

This post will concentrate on linen and cotton, and treats their history and processing separately. However, dyeing and typical uses of of linen and cotton will be discussed together.

LINEN

Linen is produced from the fibers of the common flax (Linum usitatissimum). Flax provides both oil (known as linseed), edible seeds, and fibers. As a bast fiber, the length of the raw fiber is determined by the height of the flax plant when harvested.

(As a sidenote, nettle is a bast fiber similar to linen. In archaeological finds, it can be very difficult to differentiate between flax and nettle by eye or even by microscope. It does seem, though, that nettle has been used in northern, central and eastern Europe, e.g. among Finnic tribes, at least from 2500 BCE onwards. For example, the Oseberg ship burial apparently included some nettle fragments. The processing of nettle follows in broad strokes that of linen, except nettle doesn’t necessarily need to be retted. However, the loss of plant material during processing is greater, i.e., even less spinnable fiber is gained than from flax.)

Origins of Linen Production

The world’s earliest extant linen remnants are tens of millenia old. The Upper Paleolithic Dzudzuana Cave in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia was inhabited intermittently during several periods dated to approximately 32,000-26,000 / 23,000-19,000 / 13,000-11,000 BCE, and has preserved dyed and knotted flax fibers (either twisted or spun) used for hafting stone tools, weaving baskets, or sewing garments.

Over time, first in the Fertile Crescent region, humans domesticated flax, focusing on taller plants with fewer branches and pods but longer stems that yielded more fiber. Cultivation seems to have started in the Near East around 8000-7000 BCE. In Turkey and Palestine, the use of flax dates back to at least the 7th millennium BCE.

The oldest known piece of linen cloth, dated to c. 7000 BCE, was found at Çayönü in southeastern Turkey. From Nahal Hemar Cave near the Dead Sea in Israel’s Judean Desert were found scraps of linen yarn and fabric, produced with twining, knotting, and looping techniques, including the remains of what appears to be some type of headgear, dated to 6500 BCE or thereabouts.

There is evidence for linen production in Egypt approx. 5500 BCE and for flax cultivation 4000 BCE or so, and for the latter on an industrial scale from around 2000 BCE onwards.

Also in Europe, flax cultivation at least from 4th millennium BCE is plausible. For example, numerous artefacts to do with textile production plus finished products like fabrics and netting dating between 3900 and 800 BCE have survived in late Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in eastern Switzerland and Germany. In southern Spain, near Córdoba, a 4th to 3rd millennium BCE burial deposit (five spliced-yarn flax fragments) in a small cave at Peñacalera in the Sierra Morena hills preserved the oldest examples of loom-woven textiles in the Iberian Peninsula. In Italy, linen textile fragments found at Lucone di Polpennazze have been dated to Early Bronze Age (2000 BCE or so).

Types of Linen

In modern commercial linen production, fibers aren’t formally graded by international standards like for example silks are. However, as a general rule, the better the quality of a linen yarn is, i.e., the longer the fibers in the yarn, the higher quality fabric can be woven from it. Tow-based yarns are coarser and rougher.

These days, the best fibers are used for lace, fabrics (e.g. shirt or suits), and bed sheets. Coarser grades are used for twine and rope, and historically for canvas and webbing.

Collecting and Processing Linen into Useable Forms

Cultivating flax starts from gathering seeds as well as sowing and weeding the fields. Harvesting modern flax usually happens 90 to 100 days from planting. Uprooting the plants by hand (pulling) yields the longest stems (i.e., the longest possible fibers) but is slower than harvesting with a blade or a machine.

Once harvested, seeds are removed from the stalk (rippling). Next the stalks are soaked in water (retting) to dissolve lignin and pectin and loosen the fibers. Care must be taken not to over-ret the stalks and by so doing damage (rot) the fibers. Depending on the method used, retting may take from several days up to three weeks.

It’s also possible to leave linen unretted. This so-called green linen (or green flax) is stronger and stiffer than retted linen. Nowadays it’s used as the raw material for utility textiles such as sails, packing materials, and other functional products.

Retted, dried flax is ready for breaking and scutching. Breaking is done with a wooden instrument (a sawhorse-like set of hinged wooden blades called a brake), or, even more simply, something club-like to remove the outer rotted stalk. In scutching, bundles of flax stems are beaten or struck with a long wooden knife (swingle) to separate the woody parts of the stem from the fibers.

The last step before linen can be spun is heckling or hackling, a process similar to the carding of wool in which combs or brushes are used to straighten and align the fibers; heckling also removes the final remains of the stem (tow), which can itself be re-hackled and/or spun into a coarse yarn.

An alternative technique to spinning, likely the oldest form of yarn making with flax and other bast fibers, is known as splicing. There are several variations (for example, rolling fiber ends between thumb and index finger) depending on material and local traditions. In broad terms, splicing means joining strips of fibers individually (end to end) or layered together in a thin bunch, often after having been stripped from the plant stalk directly without (or with only minimal) retting. Spliced yarn is weaker at the splice point and is often reinforced by plying. There is some evidence to suggest that the change from spliced to spindle-spun yarn is linked to fiber length (i.e., an alteration in the plant), quite possibly the result of conscious selection by humans.

Linen is stronger wet than dry, so it’s easier to spin damp using a spray bottle, or regularly dipping fingers in a water bowl. Drop spinning (spindle spinning with a whorl) and supported spinning (rolling against the thigh) are both ancient options.

Modern weavers recommend higher humidity also when weaving linen. Another factor to pay attention to is tension to avoid snapping the warp, since linen is not as elastic a fiber as for example wool.

Suggested prehistorical spinning and weaving speeds can be gleaned from research and experimenting. Two academic analyses in Denmark done by expert spinners on flax averaged about 24-33 meters and 55 meters per hour, respectively. Weaving a 95 cm wide linen tabby for a reconstruction of the so-called Viborg Shirt at Ribe Viking Centre took approx. 37 hours per meter (not including setting up the loom). Although the processing of flax is more complicated than that of wool, the extra work is still a fraction of the total labor spent to produce wearable clothes; the majority of time still goes to spinning and weaving.

COTTON

The 50 or so wild cotton (Gossypium) species are found in nearly all tropical areas and can grow as tree, bush, or grass. The plant was independently domesticated on both sides of the Atlantic. Cotton is currently enormously important as a commodity and textile material.

Origins of Cotton Production

In the Indian subcontinent, the earliest extant cotton finds have been dated to 5500-5000 BCE. Spinning probably started by around 3000 BCE at latest. India had the monopoly for cultivating cotton till approximately 2000 BCE, after which cultivating spread to the Persian Gulf and Asia, and later to Egypt, Greece, Malta, and the Roman Empire.

The Incas and Mayas also used cottons, and there recent archaeological research has identified the use of cultivated cotton (Gossypium barbadense) in the ancient Andes dating back to at least 7800 years ago. The so-called Paracas Textile is a cloak made from cotton and camelid fiber, produced by the Nasca culture around 100-300 CE, and one of the most renowned Andean textiles in the world.

By 4th or 5th centuries CE, areas further from the core cotton production areas had also picked up the skill; for example, in Kara-tepe, a pre-Islamic site near the Aral Sea in northwestern Uzbekistan, cotton seeds were found in amounts too numerous for them to be casual debris. By early 600s CE in the kingdom of Khotan (in the Tarim basin in Xinjiang, northwestern China), most people had moved away from wearing wool or fur and dressed in light silks or white cotton.

It also seems that Lower Nubia in Africa (roughly modern southern Egypt to northern Sudan) had developed its own cotton industry using their native variety of Gossypium herbaceum, sometimes referred to as ancient Nubian cotton, by 400 CE or so.

Types of Cotton

Currently there are about ten cotton cultivars of commercial viability. Most of the wild varieties have too short fibers and are, therefore, completely useless for making thread. (It’s difficult if not impossible to spin plant fibers shorter than 10 mm.)

The most important modern subspecies are Gossypium hirsutum, which is native to Central America, and Gossypium barbadence from Ecuador and Peru. The original South Asian variety is called Gossypium arboreum and there is evidence of its cultivation already in the Indus Valley civilization.

As a plant fiber, cotton’s most important component is cellulose (unlike protein in animal fibers). Cotton can also contain minor amounts of waxes, fats, pectins, and water. The quality of cotton depends largely from genetics, but growing conditions, especially humidity, also have an impact.

Grading cotton involves multiple attributes (color, purity, fiber length, fineness, strength, etc.) and there are many international standards. Purity, which refers to the amount of stem, leaf, and seed remnants (trash particles) among the fiber, is another important factor. Impurities can be seen as dark spots in the fabric.

One of the most important factors in cotton grading is fiber length. Extra long varieties are those with fiber length over 35 mm, long 30-35 mm, medium long 15-30 mm, and short 10-20 mm. The fibers’ fineness is in direct relationship to their length: the longer the fiber, the finer it is.

Collecting and Processing Cotton into Useable Forms

The cultivation of cotton takes about 120 days to develop from sowing to harvest. The difference between day and night time temperatures should be as small as possible for optimal yields, and high humidity and strong sun benefit seed growth. Cotton plants are not the easiest of crops, because they are susceptible to pests, molds, and plant and fungal diseases.

Cotton fibers (lints) grow inside a seed pod (boll) mingled with seeds. The seed pod surface is covered by shorter nap-like fibers (fuzz). These days, each seed contains approximately 10,000-20,000 fibers. Once seeds ripen, the bolls open and fibers burst out; the seed pods are then easy to pluck off. For the majority of cotton cultivation’s history, harvesting was slow because it took place by hand.

Once the seed pods have been collected, they need to be dried. Then fibers are pulled from the bolls (ginning), and contaminant plant material is separated from fibers (cleaning). Before the invention of cotton gins in the late 1700s, this was all done by hand. (From c. 400 CE onwards, first in India, the process got a little faster with the help of handheld roller gins.)

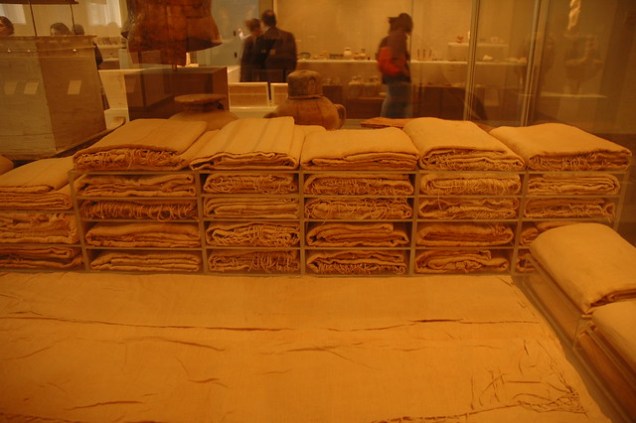

In modern processing, the residual fibers after ginning (linters) can be used to make paper and as a raw material for semi-synthetic fibers like rayon, viscose, or modal. Cleaned cotton fibers are graded and baled for transport.

Prior to spinning, cotton is carded like wool to align the fibers. The trace amounts of waxes in cotton help keep the fiber softer and more elastic, which make it easier to spin. In modern processing, the waxes are therefore removed only after spinning.

Cotton is more difficult to spin by hand than wool, since its fibers are short and don’t tend to adhere to each other as readily. Modern hand spinners recommend making a thinner yarn with more twist for a more stable end product and spinning much faster than they normally would.

DYEING PLANT FIBERS

Plant fibers withstand hot dye baths better than wool and silk, but are in general more difficult to dye. There nevertheless exists a long history of dyeing plant fibers. For example, one of the Peñacalera linen fragments mentioned above, dating to approx. 2500-2300 BCE, was exceptionally fine and dyed with cinnabar (a red mineral).

As a rule of thumb, plant fibers require mordanting beforehand, and are a good fit for tannin mordants. The degree of bond and colorfastness (fade-resistance) depend on the fibers and dyes used. Dyeing takes approximately 14 liters of water per 1 kg of linen or cotton yarns.

Undyed, unbleached linen has a yellowish to grayish brown color. Cotton tends to be white, but there are also varieties of pale yellow to brown or reddish hue. Cotton and linen require more dyestuff to achieve deep or vibrant colors, because they dry three values lighter than when wet. (For example, cotton dyed with the same directions as wool will produce a paler and more subdued color.)

TYPICAL USES OF PLANT FIBERS IN CLOTHING

When linen or cotton were first introduced to a new area, they were often reserved for high-status uses such as burial goods or Sunday best. With time and increased imports or the start of local production, the new materials became common enough even for menial purposes.

Since their strength increases when wet, both linen and cotton have long been used in contexts where that is a benefit (e.g. fishing nets and other such utility textiles). Cotton has also been applied for sewing or as a trim. In Iron Age Finland, threads made from linen, hemp, or nettle were used in sewing (e.g. of leather knife sheaths) or as warp for tablet-woven bands. In later periods, too, cotton was used as warp when weaving fabric (e.g. silk or wool) to increase durability. Historically, linen has been long used for underclothes, bed sheets, and table linen.

Under woollen outer clothes, plant fibers can be worn as the layer closest to skin for comfort, but they make poor insulation on their own. Multiple layers trapping air between them do, however, provide some benefit, as does napping the fabric (e.g. flannel), or fluffier or multi-ply yarns.

Plant fibers don’t pill or form an electrostatic charge (static) as readily as wool. They also tend to be fairly heavy and bend or wrinkle easily. (Compare them with paper, which is also made of cellulose.) Linen is stiffer, stronger, and more absorbent than cotton but even less elastic, meaning that wrinkles show very well in it. Linen has excellent heat conductivity, plus—thanks to its stiffness—is less likely to cling to skin, which are desirable qualities in humid or hot circumstances.

Linen tolerates high temperatures especially when wet (i.e., it can be ironed on high heat effectively with steam or through a damp cloth), but prolonged dry high heat will start breaking the fibers down, which happens at 260-320 C. Linen doesn’t handle mechanical stress (rubbing) very well, is susceptible to mildew and is more difficult to bleach than cotton. Linen is also shinier, almost silky, and dries fast. Linen tolerates direct sun better than cotton, and because of the smoothness of the linen fibers, it’s somewhat resistant to dirt. Linen’s poorer capacity to handle rubbing makes it a more challenging choice for utility clothing, but its higher tolerance for heat is often useful.

Cellulose in general is good at retaining moisture, and cotton can hold moisture without feeling wet, which makes it a good fabric to wear next to the skin. However, it’s also relatively inelastic and dries slowly, slower than linen. On the other hand, cotton handles rubbing and bending better than linen.

Cotton also tolerates heat pretty well, although not quite as well as linen: from 120 C upwards the fibers get damaged (reduced strength, yellowing), thermal decomposition starts soon after, and the fibers finally break down at 240 C. Prolonged direct sun can also damage cotton fibers. Cotton burns like paper: it ignites easily, burns fast, and leaves a paper-like ash residue.

Common uses for the softer plant fibers both historically and in pre-historic eras include miscellaneous homewares and garments: wrappings for burials, swaddling and diapers, bandages, underclothes of various forms, tunics and shirts, dresses and skirts, wimples and other headwear.

Underclothes might be made from coarser quality material, since they typically remain unseen, or an underlayer might a combination of two fabrics, the finer being visible while the rougher remaining hidden by overclothes. (Although made from wool, the reconstructed Iron Age Kaarina woman’s underdress from southwestern Finland exhibits this feature.)

How It Happens looks at the inner workings of various creative efforts.

One thought on “Making Clothes 6: Linen and Cotton”

Comments are closed.