When you’re designing a settlement for your player characters to visit, one thing you might want to include is local religious establishments like temples and shrines. In a world where divine beings actively grant powers to their followers, adventurers can visit these establishments looking for magical services, just like they might head to a tavern to listen for rumors or go to the local blacksmith to get their armor repaired. Here’s a homebrewed guide to temple services, suitable for Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition (2024), that you can use or adapt for your own games.

Temples in town

The first step is to determine what kind of holy places exist in the town you’re creating. Not all gods are worshiped everywhere, and not every settlement can support a large religious sector.

Holy places come in three sizes: shrine, temple, and grand temple.

A shrine is a small, humble place where the faithful can make offerings and present prayers to the gods that matter in their daily lives. A shrine typically does not have a full-time staff performing rituals, but one or two dedicated caretakers who make sure that it stays tidy and welcoming. Local people will know who to go to if some special services are needed. A shrine and its custodians can offer only services of rank 1.

A temple is a larger structure with a dedicated full-time staff of priests and acolytes. Regular religious rituals are carried out here, and there is usually someone on hand who can see to the needs of worshipers and visitors in between their duties to the god. A temple can offer services up to rank 2.

A grand temple is a community unto itself, containing a sanctuary for the god, treasuries for storing valuable offerings, and residences for a full-time staff of priests, along with the kitchens, workshops, storage sheds, and other mundane necessities for keeping the community going. A full hierarchy attends the grand temple, from the high priest and hierophants down to the acolytes learning their first prayers and the workers supplying the priests’ daily needs. Receiving visitors and attending to their religious needs is part of the routine work of the grand temple, and some of its staff are dedicated to doling out the god’s favors to adventurers and other folk in need. A grand temple offers all services.

Each religious institution in a town also serves one particular god and belongs to that god’s divine domain. This homebrew system includes options for gods in the domains of Death, Knowledge, Life, Light, Nature, Tempest, Trickery, and War, but you can use these examples as a basis for adding other domains as your setting requires.

When you are designing a settlement, it shouldn’t be too hard to decide what sort of holy places can be found there: a small village in the woods may not have much more than shrines for Life and Nature deities, while a huge port city probably has temples for every domain and a grand temple for a Tempest god.

If you want to randomly generate your settlement’s places of worship (either to save yourself a little thinking effort, or just because math rocks going clicky-clack is fun) here’s a couple of tables you can use.

First, roll 1d6 and adjust the roll depending on the size of the settlement, from -4 for a tiny village to +4 for a huge metropolis.

| Adjusted roll | Religious institutions in town |

| -3 | None |

| -2 | 1 shrine |

| -1 | 1 shrine |

| 0 | 2 shrines |

| 1 | 3 shrines |

| 2 | 4 shrines |

| 3 | 4 shrines, 1 temple |

| 4 | 3 shrines, 2 temples |

| 5 | 2 shrines, 3 temples |

| 6 | 1 shrine, 4 temples |

| 7 | 5 temples |

| 8 | 5 temples, 1 grand temple |

| 9 | 6 temples, 1 grand temple |

| 10 | 6 temples, 2 grand temples |

For each religious institution in your settlement, roll 1d8 to determine which domain it belongs to, rerolling any rolls that give the same result as one already rolled.

| 1d8 | Domain |

| 1 | Death |

| 2 | Knowledge |

| 3 | Life |

| 4 | Light |

| 5 | Nature |

| 6 | Tempest |

| 7 | Trickery |

| 8 | War |

Services available

The tables below list the services available in each domain, the rank of each service, and its cost. A description of all services is given after the tables.

The cost given in the tables below is for characters who wish to pay for services in cash, and includes the cost of any necessary material components, which the priest performing the service provides. As an alternative, some other means of payment are suggested in the next section.

Services are granted to the character requesting and paying for them, or to another creature or object that character designates. The recipient of a service knows what effect they are receiving, and a service fails if the recipient is unwilling to receive it. Only one service can be active on a given creature or object at a time, but one creature can carry multiple objects with different services active on them.

Services marked with an asterisk (*) are spells found in the Player’s Handbook or the System Reference Document 5.2.1. A brief description is given below for convenience, but see one of those sources for fuller information if needed. If a character receives one of these spells as a service, apply the following conditions:

- The spell is cast at its lowest level.

- The spellcaster’s ability is Wisdom, and their ability modifier is +4.

- A spell provided as a service does not require concentration from either the priest providing it or the creature receiving it.

- A spell cast as a service can only affect the creature who received the service or an object they carry, even if the spell normally allows its caster to choose another or multiple targets.

- Any spell whose duration is either Instantaneous or 12 hours or longer takes effect exactly as listed in the spell description as soon as the service is provided.

- Any spell that has a duration more than Instantaneous but less than 12 hours does not take effect immediately. The service instead creates an aura of magical potential around the receiving creature which lasts for 24 hours. At any time during that 24 hours, the creature may take a Magic action to activate the spell. The spell immediately becomes active and lasts for its full duration.

Death

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Death.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Detect Poison and Disease* | 50 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of the Grave | 5 GP |

| 2 | Gentle Repose* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Departed | 125 GP |

| 3 | Raise Dead* | 700 GP |

| 3 | Speak with Dead* | 100 GP |

Knowledge

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Knowledge.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Detect Magic* | 50 GP |

| 1 | Detect Poison and Disease* | 50 GP |

| 1 | Identify* | 60 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of Sagacity | 10 GP |

| 2 | Augury* | 80 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Wise | 50 GP |

| 3 | Sending* | 100 GP |

| 3 | Speak with Dead* | 200 GP |

| 3 | Tongues* | 200 GP |

Life

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Life.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Bless* | 25 GP |

| 1 | Cure Wounds* | 1 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of Healing | 5 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Protector | 50 GP |

| 2 | Lesser Restoration* | 75 GP |

| 2 | Protection from Poison* | 125 GP |

| 3 | Protection from Energy* | 200 GP |

| 3 | Raise Dead* | 700 GP |

| 3 | Remove Curse* | 100 GP |

Light

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Light.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Bless* | 25 GP |

| 1 | Cure Wounds* | 1 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of Flame | 5 GP |

| 1 | Shield of Faith* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Augury* | 80 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Illuminated | 50 GP |

| 2 | Magic Weapon* | 125 GP |

| 3 | Dispel Magic* | 100 GP |

Nature

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Nature.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Cure Wounds* | 1 GP |

| 1 | Detect Poison and Disease* | 50 GP |

| 1 | Goodberry* | 25 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of the Serpent | 5 GP |

| 1 | Longstrider* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Gentle Repose* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Wild | 50 GP |

| 2 | Protection from Poison* | 125 GP |

| 3 | Water Breathing* | 100 GP |

Tempest

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Tempest.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Cure Wounds* | 1 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of the Storm | 5 GP |

| 1 | Longstrider* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Winds | 25 GP |

| 2 | Magic Weapon* | 125 GP |

| 3 | Water Breathing* | 100 GP |

Trickery

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of Trickery.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Detect Poison and Disease* | 50 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of Cunning | 10 GP |

| 1 | Protection from Evil and Good* | 75 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Dissembler | 50 GP |

| 2 | Lesser Restoration* | 75 GP |

| 3 | Dispel Magic* | 100 GP |

| 3 | Remove Curse* | 100 GP |

| 3 | Tongues* | 200 GP |

War

The following services are available from a shrine, temple, or grand temple of a deity of War.

| Rank | Service | Cost |

| 1 | Bless* | 25 GP |

| 1 | Cure Wounds* | 1 GP |

| 1 | Lesser Blessing of Wrath | 5 GP |

| 1 | Shield of Faith* | 50 GP |

| 2 | Grace of the Marauder | 100 GP |

| 2 | Magic Weapon* | 125 GP |

| 3 | Protection from Energy* | 200 GP |

Descriptions of Services

The ranks of services and the domains which can offer them are given in parentheses after the name for reference. Services marked with an asterisk (*) are spells found in the Player’s Handbook or the System Reference Document 5.2.1. A brief description is given below for convenience, but see one of those sources for fuller information if needed.

Augury* (2 – Knowledge, Light)

- School: Divination

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Consult a divine force about a specific course of action and receive a positive or negative omen.

Bless* (1 – Life, Light, War)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 1 minute

- Add 1d4 whenever you make an attack or save roll. (Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Cure Wounds* (1 – Life, Light, Nature, Tempest, War)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Heal 2d8+4 Hit Points.

Detect Magic* (1 – Knowledge)

- School: Divination

- Duration: 10 minutes

- Become aware of magical effects within 30 feet.

Detect Poison and Disease* (1 – Death, Knowledge, Nature, Trickery)

- School: Divination

- Duration: 10 minutes

- Become aware of any source of poison or disease within 30 feet.

Dispel Magic* (3 – Light, Trickery)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Ends one magical effect of level 3 or lower.

Gentle Repose* (2 – Death, Nature)

- School: Necromancy

- Duration: 10 days

- A recently deceased creature is protected from decay and becoming Undead.

Goodberry* (1 – Nature)

- School: Conjuration

- Duration: 24 hours

- Create 10 berries, each of which heals 1 Hit Point and provides nourishment for one day.

Grace of the Departed (2 – Death)

- School: Necromancy

- Duration: 24 hours

- Whenever a spell you cast causes a creature to make a Constitution saving throw, it does so at Disadvantage.

Grace of the Dissembler (2 – Trickery)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 24 hours

- You have Advantage on Charisma (Deception) and Dexterity (Stealth) checks.

Grace of the Illuminated (2 – Light)

- School: Evocation

- Duration: 24 hours

- You may use a Magic action to cast the spell Light, requiring no material components. You may cast this spell any number of times while this service lasts. When you cast Light using this service, Wisdom is your spellcasting attribute, and if your Wisdom modifier is less than +4, it is considered +4 for purposes of this spell.

Grace of the Marauder (2 – War)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- You gain a +1 bonus to your attack rolls and AC.

Grace of the Protector (2 – Life)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: 24 hours

- Whenever you roll dice to restore Hit Points to any creature, that creature also receives Temporary Hit Points equal to the highest number on any one of the dice you rolled.

Grace of the Wild (2 – Nature)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 24 hours

- You have Advantage on Intelligence (Nature) and Wisdom (Survival) checks.

Grace of the Winds (2 – Tempest)

- School: Evocation

- Duration: 24 hours

- Once per turn, when you deal damage to another creature, you may move your target up to 10 feet away from you or move yourself up to 10 feet away from your target. (This movement does not provoke opportunity attacks.)

Grace of the Wise (2 – Knowledge)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 24 hours

- You have advantage on Intelligence (Arcana) and Intelligence (History) checks.

Identify* (1 – Knowledge)

- School: Divination

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Learn the properties of one magical object.

Lesser Blessing of Flame (1 – Light)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on one weapon of your choice. That weapon deals either Fire or Radiant damage in addition to any other types of damage it deals (you choose the type of damage when receiving the service).

Lesser Blessing of Cunning (1 – Trickery)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 24 hours

- Choose 1 skill based on Dexterity or Charisma. An enchantment is placed on an item you carry. Any creature carrying that item gains a bonus equal to their proficiency bonus to d20 checks made with that skill.

Lesser Blessing of Healing (1 – Life)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on an item you carry. Whenever a creature carrying that item casts a spell with a spell slot that restores Hit Points to any creature, that spell restores a number of additional Hit Points equal to the caster’s proficiency bonus.

Lesser Blessing of Sagacity (1 – Knowledge)

- School: Enchantment

- Duration: 24 hours

- Choose 1 skill based on Intelligence or Wisdom. An enchantment is placed on an item you carry. Any creature carrying that item gains a bonus equal to their proficiency bonus to d20 checks made with that skill.

Lesser Blessing of the Grave (1 – Death)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on one weapon of your choice. That weapon deals either Necrotic or Psychic damage in addition to any other types of damage it deals (you choose the type of damage when receiving the service).

Lesser Blessing of the Serpent (1 – Nature)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on one weapon of your choice. That weapon deals either Acid or Poison damage in addition to any other types of damage it deals (you choose the type of damage when receiving the service).

Lesser Blessing of the Storm (1 – Tempest)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on one weapon of your choice. That weapon deals either Lightning or Thunder damage in addition to any other types of damage it deals (you choose the type of damage when receiving the service).

Lesser Blessing of Wrath (1 – War)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- An enchantment is placed on one weapon of your choice. That weapon deals either Force or Radiant damage in addition to any other types of damage it deals (you choose the type of damage when receiving the service).

Lesser Restoration* (2 – Life, Trickery)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Remove Blinded, Deafened, Paralyzed, or Poisoned conditions.

Longstrider* (1 – Nature, Tempest)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 1 hour

- Your Speed increases by 10 feet.

Magic Weapon* (2 – Light, Tempest, War)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 1 hour

- A weapon you touch becomes a magic weapon with +1 to attack and damage rolls.

Protection from Energy* (3 – Life, War)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: 1 hour

- Gain Resistance to one damage type: Acid, Cold, Fire, Lightning, or Thunder.

Protection from Evil and Good* (1 – Trickery)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: 10 minutes

- You are protected against Aberrations, Celestials, Elementals, Fey, Fiends, and Undead. ( Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Protection from Poison* (2 – Life, Nature)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: 1 hour

- Gain Resistance to Poison damage and Advantage on saving throws against the Poisoned condition. ( Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Raise Dead* (3 – Death, Life)

- School: Necromancy

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Revive a creature that has been dead less than 10 days.

Remove Curse* (3 – Life, Trickery)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Remove all curses affecting an object or creature.

Sending* (3 – Knowledge)

- School: Divination

- Duration: Instantaneous

- Send a message of 25 words or less to another creature.

Shield of Faith* (1 – Light, War)

- School: Abjuration

- Duration: 10 minutes

- Gain +2 AC. (Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Speak with Dead* (3 – Death, Knowledge)

- School: Necromancy

- Duration: 10 minutes

- Ask 5 questions of a corpse.

Tongues* (3 – Knowledge, Trickery)

- School: Divination

- Duration: 1 hour

- Understand any spoken or signed language. ( Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Water Breathing* (3 – Nature, Tempest)

- School: Transmutation

- Duration: 24 hours

- Gain the ability to breathe under water. (Note: when received as a service, this spell targets only the creature that received the service.)

Alternative payment

Instead of a donation in coin, you might offer your player characters a chance to pay for their services with services of their own. This can be a good option for a cash-strapped party, and can also provide opportunities for side quests or for downtime activities to let your players practice some of their lesser-used skills. Here are some suggestions to consider:

Rank 1 services

- Entertain the children at the local orphanage for an afternoon (Life, Trickery)

- Fix a leaky roof, patch gaps in the walls, replace some broken floor tiles, or perform other simple maintenance in the temple (Nature, Tempest)

- Gather firewood for the temple from nearby woods (Light, Nature)

- Gather wild plants to restock the temple’s store of spell reagents (Knowledge, Life, Nature, Tempest)

- Participate in a solemn funeral procession for a recently deceased local hero (Death, Light)

- Play a small, harmless prank on the priests of a rival temple (Trickery)

- Recount tales of your party’s adventures to be recorded for posterity (Knowledge, Light, Trickery, War)

- Spar with some paladin trainees (Light, War)

- Tidy up the local graveyard (Death, Nature)

Rank 2 services

- Clean out a local village’s irrigation channels (Life, Tempest)

- Convince some mischievous wood sprites to move out of a sacred grove (Light, Nature, Trickery)

- Deliver needed medicines and potions to an outlying village (Life, Nature)

- Fight a demonstration duel against a band of chosen champions for paladin initiates to observe and learn from (Light, War)

- Find a ghost that has been haunting a local crypt and find out what it needs to be able to move on into the afterlife (Death, Knowledge, Light)

- Fish, hunt, and gather foods from the local wilderness for a communal feast (Life, Nature, Tempest)

- Join in the funeral games for a fallen local hero and win at least one victory in the god’s name (Death, Life, War)

- Spy on a local criminal syndicate to find out where their meeting spot is so the authorities can deal with them (Knowledge, Light, Trickery)

Rank 3 services

- Compose and stage a play about the party’s adventures for the entertainment and education of local townsfolk (Knowledge, Life, War)

- Hunt a wild beast that has been terrorizing villages the hinterlands (Light, Nature, Tempest)

- Investigate the local noble houses to determine which of them has been skimming off the temple tithes (Knowledge, Light, Trickery)

- Keep an overnight vigil in a local graveyard on a night when minor evil spirits are known to wander. Keep the spirits distracted to stop them from causing trouble. (Death, Trickery)

- Recover a lost relic last known to have been in the possession of a fallen hero, who may have since become undead (Death, Light, War)

- Seek out and defeat a minor local bandit or other troublemaker (Life, War)

- Spend a stormy night standing watch at a dangerous headland and rescue the survivors from ships that founder in the waves (Life, Light, Tempest)

- Track a noble beast that was gravely wounded but not killed in an upstart noble’s botched hunt and put the creature out of its pain (Death, Nature)

This work includes material from the System Reference Document 5.2.1 (“SRD 5.2.1”) by Wizards of the Coast LLC, available at https://www.dndbeyond.com/srd. The SRD 5.2.1 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.

This work includes material taken from the System Reference Document 5.1 (“SRD 5.1”) by Wizards of the Coast LLC and available at https://dnd.wizards.com/resources/systems-reference-document. The SRD 5.1 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.

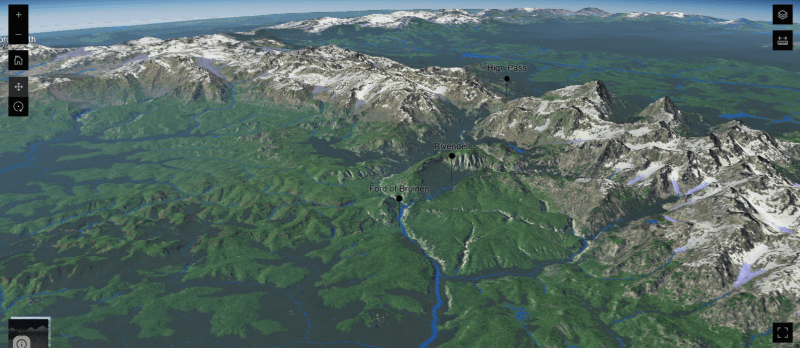

Images: Algorithmically generated images made with Night Cafe: Shrine, Temple, and Grand Temple

Of Dice and Dragons talks about games and gaming.

You must be logged in to post a comment.