Cults are a staple of modern fantasy. When you need a shadowy organization for your hero to go up against, whether they’re protecting an ancient secret or scheming to bring about the end of days, you can’t go wrong with a cult.

There are plenty of modern examples of secretive organizations that draw in forlorn or gullible people and condition them to submit to the will of charismatic leaders. Such organizations can serve as models for imagining fictional cults, but if you want to write a cult in a fantasy setting, it can be helpful to look at ancient examples. One of the oldest documented examples of a secretive religious organization in conflict with larger society is the ancient Roman cult of Bacchus.

The cult of Bacchus emerged in southern and central Italy in the late third century BCE. It was centered on the worship of the god Bacchus, a version of the Greek Dionysus associated with wine, fertility, and ecstatic release. The Italian Bacchus also borrowed some traits from the Roman god Liber, connected with grapevines, wine, fertility, and freedom. The worship of Dionysus, Bacchus, and Liber was well established as part of the state religion of the Roman republic, which by this time had solidified its control over the whole of the Italian peninsula. The cult of Bacchus was a new religious movement that drew on older traditions but offered its followers new ways of celebrating them.

Followers of this movement practiced their worship in secret, not as part of the state-sanctioned public religion. Only initiated members of the cult were allowed to join in. Unlike traditional Roman religious celebrations, which maintained distinctions between social classes and had separate roles for men and women, initiates of Bacchus included people of all genders and classes who mixed together indiscriminately in their rites. Celebrations were raucous nighttime affairs that featured feasting, drinking, music, and dance.

The Roman elite was scandalized by the popularity of this religious movement. All the surviving sources describing its activity come from this hostile perspective and include lurid suggestions that the Bacchic revelers were practicing magic, engaging in wild sexual frenzies, and scheming at poisonings and other nefarious deeds. Despite these unfavorable sources, there is no reason to think that the cult of Bacchus was actually so outrageous. Seen in the context of the time, we may actually find the cult appearing in a much more favorable light.

To understand the cult of Bacchus, we need to set aside both the hostile attitude of the Roman elite and many of our modern associations with the term cult. While we associate the term today with secretive, manipulative organizations, cult, in its historic use, refers simply to the set of practices that are appropriate to the worship of a particular god or divine entity. All ancient gods received cult from their worshipers, from the official ceremonies for gods of the state to the everyday rituals that attended family and household spirits. Although the cult of Bacchus carried out its rituals in private, there is no indication that the organization was manipulative or coercive, or that members were isolated from the rest of society. In fact, in many ways, the cult offered a positive experience for its members.

Italy in the late third century BCE was recovering from the devastation of the second Punic War. From 218 to 204 BCE, the Carthaginian army led by Hannibal operated largely unchecked in Italy. The effects of war were far-reaching. Many young people from Rome’s Italian subjects were called up to fight in Rome’s legions, some never coming home again. Roman and Carthaginian armies alike ravaged farms up and down the peninsula. In the aftermath of the war, many small farms faced ruin, and a lot of Italian families had little choice but to sell their land to the aristocratic elite at whatever price they could get and move into cities like Rome looking for any work they could find to scrape together a living. Italy in the late third and early second centuries BCE had a vast population of poor people barely getting by, dislocated by war and poverty from their ancestral homes, and resentful of the elite who had come out of the war riding high on plunder and foreign slaves.

The cult of Bacchus offered relief from the pressures of life—if not a hope for a better world, at least a temporary distraction from the troubles of this one. It helped people who had been displaced from deeply rooted ties of family and community find new connections outside the limitations of gender and class. For people who had little joy in their lives and faced a hard daily grind just to eat, the appeal of a celebration full of food, music, and dance was strong. It’s not hard to understand why the cult gained a following in post-war Italy.

It’s also not that hard to see why the Roman aristocracy reacted with such alarm and hostility. The Second Punic War had hit Rome hard. Even though the Romans emerged victorious over Carthage in the end, a generation of potential recruits for Rome’s armies was killed or wounded in the fighting. Rome’s resources were stretched to the limit. What’s more, the war exposed weaknesses in Rome’s hold on Italy. Hannibal’s strategy was to deny Rome resources and fighting power by helping its subjects in Italy rebel. Not all of Italy took Hannibal up on his offer, but enough cities did, especially the Greek cities of southern Italy, to make the Roman elite nervous about their ability to maintain control of the peninsula. Since the cult of Bacchus particularly appealed to the southern Italian Greeks, it doesn’t take much to see why the Roman aristocracy in the years after the war saw disaffected poor Italians gathering together in secret and challenging established social lines as a dangerous thing that needed to be stamped out. The Roman state aggressively suppressed the cult of Bacchus, the first documented example in Western history of a religious movement persecuted by the state.

The cult of Bacchus may not fit the mold of the classic sinister fantasy cult, but understanding the context in which it arose and the forces which drew people to it can help with the worldbuilding for a story in which a cult may not be so benign. Desperate times drive people to find community, relief, and happiness in whatever ways they can. The cult of Bacchus was in reality a benevolent organization that provided much-needed fellowship, but unscrupulous people and organizations can take advantage of the same needs for darker ends.

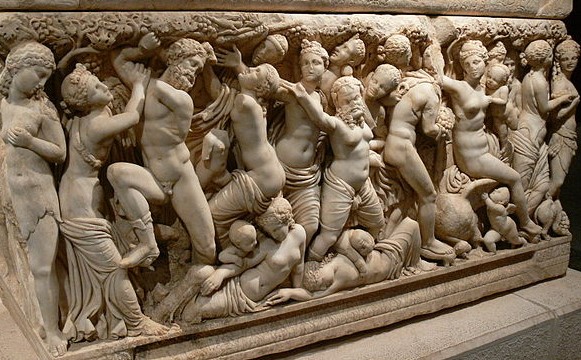

Image: A scene of Bacchic revelry from a Roman sarcophagus, photograph by Wolfgang Sauber via Wikimedia (currently Anatalya Archaeological Museum; 2nd c. CE; marble)

History for Writers looks at how history can be a fiction writer’s most useful tool, from worldbuilding to dialogue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.